Kobudo/Classical Weapons Training

Kobudo- The Weapons of Okinawan Karate

Kobudo is taught to be supplemental and voluntary in the Karate programs.

Kobudo is taught to be supplemental and voluntary in the Karate programs.

The bo, or stick is probably one of the first weapons that mankind used to defend or hunt. It could easily be found, was not to difficult to handle, and could be used for multiple purposes. In Okinawa, the bo probably originated from a farm tool called tenbin. It is a stick held across the shoulders, on which fish or water buckets could be hung. It could also be originated from walking sticks monks used to ease hiking and eventually defend themselves. The techniques executed with the bo, were probably developed very early in history, and were probably refined after the Heian Era (around 1127 AD).

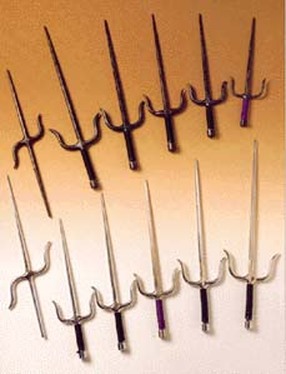

Again, the saï was a simple farm instrument which the peasants turned to their advantage once they were forbidden to carry weapons. Usually, the saïs are used in pairs. A third saï was hidden in the obi (belt) and was used to replace one saï that was thrown at the charging enemy. If the throw was successful, the fight could be over all at once. If not, the distraction could be just enough to get close to stab with the saï or to counter an attack and win the battle. Originally, the saï was made out of 2 separate parts: the stem and the curved prongs. These 2 parts were then pounded together in a process similar to that used by swordsmiths. Around late 19th century, another method was used. A finished saï would serve to create a saï shaped cavity in the ground. Molten iron was poured into this shape, producing a perfect twin of the first saï when the iron had hardened. Rough edges were removed and afterwards the saï was polished.

Like the other kobudo weapons, tonfa was used as a working tool, before being a weapon. The tonfa was an arm of a millstone for preparing grain, which could easily be removed. The main part of the tonfa, the shaft, consists of a large hardwood body, about 50 to 60 centimeters in length, and a smaller cylindrical grip secured at a 90 degrees angle to the shaft, about 15 centimeters from one end.

The kama was a tool used to cut weeds and bring in the crop. It was a very simple but very sharp and potentially deadly weapon. Its structure however made it very weak when attacked with heavy blows directly to the blade. Therefore, there has been a redesign of the weapon, which is called natagama. It is stronger in its construction, because the blade runs through past the curve of the normal kama and all the way down into the handle. This makes the cutting edge bigger, and above all, the previous weak point where the sickle was attached to the stick has disappeared.

Japanese Katana (Samurai) Sword

Supplemental (Training in)

Supplemental (Training in)

Traditional training is offered to only those most dedicated student(s)

Hanshi Conley's katana made by the sword smith Mori Hisa in 1580. (Translation and dating by Fred Lohman & Associates)

The production of swords in Japan is divided into specific time periods: jokoto (Ancient swords, until around 900 A.D.), koto (old swords from around 900-1596), shinto (new swords 1596-1780), shinshinto (new new swords 1781-1876), gendaito (modern swords 1876-1945), and shinsakuto (newly made swords 1953-present).

The first use of "katana" as a word to describe a long sword that was different than a tachi is found in the 12th century. These references to "uchigatana" and "tsubagatana" seem to indicate a different style of sword, possibly a less costly sword for lower ranking warriors. The evolution of the tachi into the katana seems to have started during the early Muromachi period (1337 to 1573). Starting around the year 1400, long swords signed with the "katana" signature were made. This was in response to samurai wearing their tachi in what is now called "katana style" (cutting edge up). Japanese swords are traditionally worn with the signature facing away from the wearer. When a tachi was worn in the style of a katana, with the cutting edge up, the tachi's signature would be facing the wrong way. The fact that swordsmiths started signing swords with a katana signature shows that some samurai of that time period had started wearing their swords in a different manner. The rise in popularity of katana by samurai is believed to have been due to the changing nature of close-combat warfare. The quicker draw of the sword was well suited to combat where victory depended heavily on fast response times. The katana further facilitated this by being worn thrust through a belt-like sash (obi) with the sharpened edge facing up. Ideally, samurai could draw the sword and strike the enemy in a single motion. Previously, the curved tachi had been worn with the edge of the blade facing down and suspended from a belt.

The length of the katana blade varied considerably during the course of its history. In the late 14th and early 15th centuries, katana blades tended to be between 70 to 73 cm (27½ to 28½ in.) in length. During the early 16th century, the average length was closer to 60 cm (23½ in.). By the late 16th century, the average length returned to approximately 73 cm (28½ in.).

The katana was often paired with a similar smaller companion sword, such as a wakizashi or it could also be worn with the tantō, an even smaller similarly shaped sword. The pairing of a katana with a smaller sword is called the daishō. The daisho could only be worn by samurai and it represented the social power and personal honor of the samurai. (Sourced from Wikipedia.org)

The first use of "katana" as a word to describe a long sword that was different than a tachi is found in the 12th century. These references to "uchigatana" and "tsubagatana" seem to indicate a different style of sword, possibly a less costly sword for lower ranking warriors. The evolution of the tachi into the katana seems to have started during the early Muromachi period (1337 to 1573). Starting around the year 1400, long swords signed with the "katana" signature were made. This was in response to samurai wearing their tachi in what is now called "katana style" (cutting edge up). Japanese swords are traditionally worn with the signature facing away from the wearer. When a tachi was worn in the style of a katana, with the cutting edge up, the tachi's signature would be facing the wrong way. The fact that swordsmiths started signing swords with a katana signature shows that some samurai of that time period had started wearing their swords in a different manner. The rise in popularity of katana by samurai is believed to have been due to the changing nature of close-combat warfare. The quicker draw of the sword was well suited to combat where victory depended heavily on fast response times. The katana further facilitated this by being worn thrust through a belt-like sash (obi) with the sharpened edge facing up. Ideally, samurai could draw the sword and strike the enemy in a single motion. Previously, the curved tachi had been worn with the edge of the blade facing down and suspended from a belt.

The length of the katana blade varied considerably during the course of its history. In the late 14th and early 15th centuries, katana blades tended to be between 70 to 73 cm (27½ to 28½ in.) in length. During the early 16th century, the average length was closer to 60 cm (23½ in.). By the late 16th century, the average length returned to approximately 73 cm (28½ in.).

The katana was often paired with a similar smaller companion sword, such as a wakizashi or it could also be worn with the tantō, an even smaller similarly shaped sword. The pairing of a katana with a smaller sword is called the daishō. The daisho could only be worn by samurai and it represented the social power and personal honor of the samurai. (Sourced from Wikipedia.org)